- Home

- Frankel, Jordana

The Ward Page 2

The Ward Read online

Page 2

Ugh, I groan, finally understanding that I actually need those boxes to make the climb in ten minutes.

Which means I have to get them.

I whine, facedown, little shards of concrete digging into my forehead. Can’t waste any more time, I remind myself, dropping my legs back over the side. I lower myself down, then let go of the ledge, falling the last few feet.

My feet hit the roof’s copper panels and I hear Benny laugh. Without looking, I growl at him, and rush to the farside of the tower. There, I begin stacking boxes. As they pile up, they lose their balance, so I reach for a long copper beam and prop it against the higher ones. That will keep ’em steady, I hope.

Done—everything’s in position.

I’m gonna do it, I’m hours away from being a real racer. I grin to myself and hop onto the first box, then the second, all the way up to the first ledge.

As I hug the tower and step up, the boxes jiggle underneath me, but I keep my foot firm on them. My fingers feel the brick for more cracks, and I keep climbing. When I look up, I see the final ledge. In order to reach it though, I have to lift my foot and let the boxes drop.

On the count of three, I jump. The boxes give me one last boost, and my hand finds the ledge. Then they tumble down, and I’m left hanging here, feet dangling in midair. I kick against the siding; I throw my elbows and shoulders onto the overhang. Knees swinging, teeth gritting, I clamber up the wall.

And then, I’ve made it—I’m at the top!

I whoop and I holler, punching the sky with both my fists. Remembering that this was only half the test, I look for Benny. “Time?” I call out again.

A moment passes. He doesn’t answer. Once more: “Benny, how much time?”

Still nothing . . .

Then the air starts to shake. Vibrate. Under my feet, the brick shudders.

“Renata!” Benny immediately calls. “Get down . . . Now!”

I don’t have to ask why. It’s the Blues—one of their helis, I’m sure of it. Though I’ve never seen one with my own eyes, everyone knows the warning signs. Somewhere, there’s about to be a raid. Could be a water theft, or maybe a black market drug bust—who knows.

I sit on my butt and swivel around. With my stomach to the wall, I shimmy down and drop the remaining few feet onto the next ledge. There, I repeat the process once more till I hit the ground.

At the bottom, Benny wastes no time—he grabs my elbow, drags me to a corner. Together we duck behind the brick wall that surrounds the rooftop, and wait.

“Why do you think they’re here?” I whisper, watching the dust get kicked up by the angry air. If I strain my ears, I can even hear the chop of propellers. We’ve got a clear view of the Blues’ headquarters on the West Isle from here too, but it’s useless; the heli’s already on our side of the Strait.

My skin gets the prickles.

We see it: one beamer crawling across the horizon. It’s headed for the Ward’s residential district, nicknamed the U ’cause from a bird’s-eye view, the Ward is a big ole horseshoe-shaped island of squat, mostly gray buildings. Once it was called Midtown. Now it’s in the middle of nothing, ’cept for the Hudson Strait.

Benny follows the light with his eyes until it hits the U’s western arm. Shaking his head, he answers, “Not for the races, that’s for sure. Ever since we’ve had a designated ‘racing district,’ they’ve turned a blind eye.”

He nudges me in the elbow, then points to the Ward’s southern racing quadrants, Seven through Ten. No one lives there now—it’s just an island of abandoned skyscrapers. After the Wash Out, the government left them to crumble. The buildings were so huge and so high, it was too expensive. The Restructuring teams didn’t even bother.

Now they’re a racer’s playground, good and dangerous.

“It’s stopping,” Benny says.

Just north of us, the heli hovers over Quadrant One. Then it picks up again, travels down the arm of the U. At Quadrant Three, again it stops. If I’m right, Five is next—us.

Benny and I stay silent. We watch the heli lift up and continue south. Its props blow the air wild, rocking the suspension bridges that zigzag east to west, rooftop to rooftop. For many, they double as laundry lines, and right now, thanks to whatever business that heli’s got going here, entire neighborhoods are losing their clothes. Bet the Blues haven’t even considered how much it will cost us.

I was right . . . Quad Five is next. The aeromobile is so close I can make out its slice-em dice-em props and disk-shaped belly. And the words Division Interial painted on its side, though we just call ’em the Blues.

One guy in blue dangles out the pit, a megaphone to his mouth, and moments later we can hear him. “Attention, citizens!” he shouts.

Benny and I exchange glances.

“Due to the rampant spread of the HBNC virus, also known as the Blight, Governor Voss, two hours prior, has declared a state of emergency in the Ward. Effective immediately, he has enacted the following two Health Statutes for the good of the United Metro Islets.”

I scoff at that—the cancer virus is rampant all right, but not on the West Isle. This is for their good. We’ve already got it bad.

“Statute One,” the man with the megaphone continues, “declares transmission of the HBNC virus a statewide offense, punishable by arrest. The DI will be establishing a local Ward task force responsible for randomized public testing.

“Statute Two orders the suspension of all outbound, civilian trade and travel from the Ward to the West Isle until further notice.

“That is all. Please turn to your local radio channels for more information. Thank you.”

With that, the heli churns upward, back into the sky. We watch it hurtle off into the dark, more laundry scattering in its wake, but I’m still playing over the words in my head. Didn’t quite get all of their meaning, about health statutes and whatnot.

Benny falls back against the brick siding. “I don’t believe it. . . .” he whispers to himself.

“Believe what?” He sounds so terrified.

“A quarantine. Over the entire city. In not so many words, but that’s what it is.” He pauses, brings his hand to his mouth. “I, I can’t . . . I can’t leave,” he murmurs.

Is that what that meant?

“I’m sure they’ll let you cross,” I insist. “You live there—”

Benny shakes his head. Mutters, “Perhaps . . . perhaps,” as he runs a hand through his wiry, gray hair. “I’ll contact someone tomorrow. No doubt the lines will be busy all night.” But his eyes glaze over, he’s lost in his head, and I wonder if he really is stuck here for good.

We sit together, side by side, silent.

“How can they arrest people for being sick?” I ask, ’cause that part I mostly understood. Everyone knows the word arrest.

My question shakes him out of it, barely. “Transmission,” he clarifies. “You can be sick. You just can’t get anyone else sick.”

“Oh.”

We’re back to quiet again. Above our heads, the hour hand on the clock ticks closer to eleven thirty. I don’t want to sound like I don’t care—Benny’s in a rough spot—but my mind is stuck on whether I get to race tonight. I keep quiet, though. Can’t stop my mind from being rude, but I can stop my mouth.

I don’t have to say nothing, turns out.

Benny sees me hawk-eyeing the clock, and pats my knee gently. “You’ll race tonight,” he says, though his voice is tired and sad, like he’s not really here. “After all, you did make it to the bottom in just around ten minutes.”

“You sure?” I ask, biting my lip. “I’d understand if you wanted to take care of stuff and forget about the race. Really, I would.”

And I would, I guess. If I had to, I would.

He places a palm on my head and tousles my wild, wiry black curls. “I’m sure. You knew when to turn around and start from square one, and when to keep going. You’re ready. Just be careful of those guys,” he says, pointing in the direction of the Blues’ headq

uarters on the West Isle. “They may not like patrolling the Ward because of the Blight, but if they catch you—if you do anything stupid—no hesitation, they’ll jail you.”

I look up at him, confused. “But I heard sometimes they try to make a mole out of you if you’re useful?”

“And would you like to become a mole?”

I see what he’s getting at. “Moles are sellouts,” I spit. “I’d never turn mole.”

“Then don’t do anything stupid, like stealing from freshwater stores, or nabbing treats from the Mad Ave vendors. I know what you orphans do.”

At that I grumble, checking the sky. “They won’t catch me,” I say, confident.

“Ha.” Then he looks to reconsider. “No, I’m sure they won’t. And if they did, they’d probably throw you back into the sea, such a pain-in-the-arse fish you’d make.”

I nod, hoping he’s right.

PART ONE

1

Three years later

1:00 A.M., SATURDAY

My breathing quickens and I realize I’m panting: prerace jitters. Racing is your job now, I remind myself, readying my game face in the bathroom mirror. It’s not a mask—I’ve worn it for too many years now. It’s a knife. A blade. All angles, sure to cut. I’ll smile. I’ll keep all my fear undercover.

You’re invincible, dammit.

Who else—aside from Benny, back in his prime—has won every race they’ve ever entered?

No one.

Who else is immune? Who else could ask to be tested any day of the week and pass, always?

No one.

Too bad that last thought does me no good. I’d give my blood to Aven if I could, alone and sick at home. She’s not contagious anymore, so we don’t have to worry about her getting arrested. But the virus is no less deadly just ’cause she’s not contagious. In only two months, her tumor’s grown bigger than an egg, bulging out from the base of her skull.

Someone as good as she is shouldn’t be dying. Someone like me . . . I should be dying.

You’re a sellout, my mind hisses.

At my wrist, my DI-issued cuffcomm trills: thirty minutes till flags go down. Time to check in.

The Blues don’t like it when their precious moles are late.

One quick glance to make sure the bathroom is empty, and I duck into a stall. I play around with my brass headset till it fits comfortably—a few purple and lime kinks of hair boing out the sides, but there’s no fixing that. I stopped trying for pretty long ago. Pretty won’t win races. Pretty don’t get respect.

I take a deep breath to still my nerves. I’ll never get used to this, I think, and flip open the comm. Crouched over the toilet seat, I punch in Chief Dunn’s number at headquarters, and look down into the murky water. To think—people used to fill toilet bowls with fresh. Pissing into a pot you can drink out of. Unbelievable.

The earbud crackles as I talk into the mouthpiece. “Come in, come in, Chief Dunn at HQ.”

Mole. That’s what I’ve become. The very word makes me shake, even after all this time.

Three years ago, Aven and I planned our escape from Nale’s. Aven had just started to wheeze, and we could feel the tumor. She’d be unadoptable. And no one was going to pick me for their daughter, so it made sense. I botched it all, though, “borrowed” fresh from the orphanage stores—for the road—and Nale called the Blues on us.

I was the only one they caught—Aven got left behind. A great big heli swooped down, netted me, but never even saw her, dizzy and tired a hundred feet back. Flew me away like a stork with a baby bundle, all the way to the Division Interial’s headquarters for jailing.

I wasn’t bothered by the jailing, though—no, I was more bugged that they’d take my blood, figure out I was immune, and turn me into a froggy experiment. So I offered to work for them—whatever they needed.

I asked to be a mole. Still makes me want to spit.

As it turned out, they needed someone who knew the lay of the land and could scout the Ward’s dangerous quadrants for freshwater. A racer, for instance. And here I landed in their lap: an orphan. A ward of the state. Totally disposable. If I got sick, they could find someone else.

The line sputters, levels into a low buzz. “Quadrant?” a recording prompts, and I punch “10” into my cuffcomm. Like always, the recording reminds me to report to Chief Dunn immediately after the race. As if I’d suddenly forget.

The bathroom door creaks open. Brack, I curse to myself, flipping my cuffcomm shut. Who’s in here?

I wait for the line to go dead, then hop out of the stall before anyone could’ve heard me. My mole status stays a secret. Even if I’m just looking for fresh, no one likes the Blues. I’d be hated by the other racers. More than I already am.

In walks the Dreaded Duo. Dragster girlfriends. Their platform shoes knock against the floor, and by way of the mirror’s reflection I see Tanzii first—fauxhawked, with one ear full of metal hoops, bars, and studs. Then comes Neela—all infinite legs and waterfall hair. All flaunt. No confetti-spiral do like I got. No dusky, freckled skin, or eyes that are half-open, half-closed all the time.

It kills me to say it, but the other racers have hot girlfriends.

I bet they’re even nice . . . to people they don’t hate so much, that is.

“That’s right . . . scamper off,” Tanzii, the taller of the two she-devils, hisses, running a hand through her tawny do.

And I do leave. But not because she told me to.

I step out onto the rooftop, ready.

Two feet out of the stairwell, a fist grabs for my shoulder and steers me to the rooftop perimeter.

“Not again,” I grumble, turning to see a muscly guy wearing the telltale yellow-and-black jacket. Don’t need to see his back to know what’s written there: HBNC Patrol. He’s one of the Blues’ goons, a Bouncer, here to randomly test people and then bring anyone who turns up contagious to a sickhouse.

Commission-based earnings, it’s called. Each infectious person they pick up earns them money. That way, the DI rarely risk getting sick, only hitting the Ward to make Transmission arrests.

I pull back the right sleeve of my red leather catsuit to show how many times I’ve already been tested. It don’t matter, they keep on dragging me. “Look,” I say to the guy, and wave my forearm in his face. A row of small, white X marks have been branded into the skin—proof of every VEL test I’ve ever been given. Of course, my Virus Exposure Level is, and always will be, nil.

The Bouncer ignores me as he searches my arm for the date marked under my last X.

“Not recent enough,” he growls, dropping it. Then he slips on a pair of white latex gloves and sticks me in the forearm with a tiny needle—a blood scanner—to see if I’ve got a certain amount of the virus that would mean I’m contagious.

Which I don’t.

I roll my eyes and start to tap my feet, impatient. This is a waste of my time, and even after a dozen VELs, getting the brands still hurts. Not to mention how I hate getting tested before a race—I actually use these arms. For pretty important stuff. Like, ya know—racing.

A moment later, the scanner beeps and the Bouncer takes back the device. “HBNC negative,” he informs me.

No kidding.

Flipping the scanner over, he presses a button, and we watch the tip—no bigger than my pinkie nail—glow until it’s red. I make a fist and try not to wince as he presses the blazing X and today’s date into the white of my arm.

It lasts less than a second, and then I exhale. One more welt, raw and pink, to add to the mix.

“Ren!” a voice calls from behind me. I turn around and spot Terrence to the far left.

My stomach bottoms out. He’s beneath the undercarriage of a brand-new racing mobile—an Omni, of all things. Makes me think I must’ve heard wrong, that it can’t really be Ter, but I know his close-shaved, brown head of hair too well.

His Omni’s a beaut—not to mention almost impossible to beat. But I can’t lose. The money I get from the Bl

ues keeps Aven stocked in pain meds. My earnings from the races keep us fed and alive.

Take one away and life goes from hard to impossible.

“Ter!” I shout back, ignoring the cold trickling through the zipper of my catsuit as I maneuver my way to the other side of the roof. The whole thing lays at a slant, perfect for all our mobiles to gain momentum before the first jump, but a bit awkward to be running on in my beloved Hessian boots, tassel and all.

Soon as he waves, my jealousy over his new mobile fizzles away. It’s something about his eyes, I think, that does it. They’re a bright, West Isle Astroturf green that would be shocking even if his skin weren’t a bit darker than mine, and they’re always laughing. Not to mention his baby face—Ter’s still pudgy-cheeked from childhood. It doesn’t exactly inspire fear.

No, he’s not the big bad wolf of the races. More like a lamb, if you ask me. But with this kind of mobile . . . well, anyone’s a threat. I can’t hold it against him, though. He’s never won a race in his life, and if I had the money, I’d buy an Omni to fix that too.

“Holy sweaty socks from Hell! Terrence, how did you pull this off?” I wrap my arms around him in a bear hug. Good thing he’s one of the nice guys, or I’d never let on how green I am.

“Oh, this old thing?” His dark hand gives a casual slap to the orange exterior, and he walks around the cone-shaped body. Gently, he presses his fingers into each of the front wheels, testing their pressure. Then he moves to the single back wheel. “Well, my birthday’s coming up, and my dad wanted me racing safe. Since I was gonna do it anyway.”

I nod—that’s what I think I miss most about never having had parents. The gifts.

Since I like pushing buttons, “Why don’t you tell me about your new vegetable,” I ask.

“S’cuse?”

Terrence looks perplexed.

“Your carrot. She’s orange, ain’t she? I would’ve given her a paint job before the big day, but that’s just me. Plus the shape, it’s very . . . carrot-like.”

“Well then, she’ll be a swimming carrot,” he says with a smile, and I should’ve known better—Ter has no buttons. Always been hard to anger. “This is a grade A Omni6000 mobile. Retractable wheels, airtight interior. Even got a backseat.”

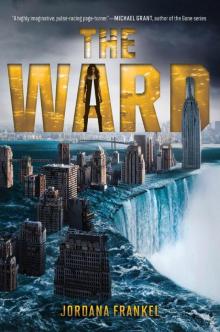

The Ward

The Ward